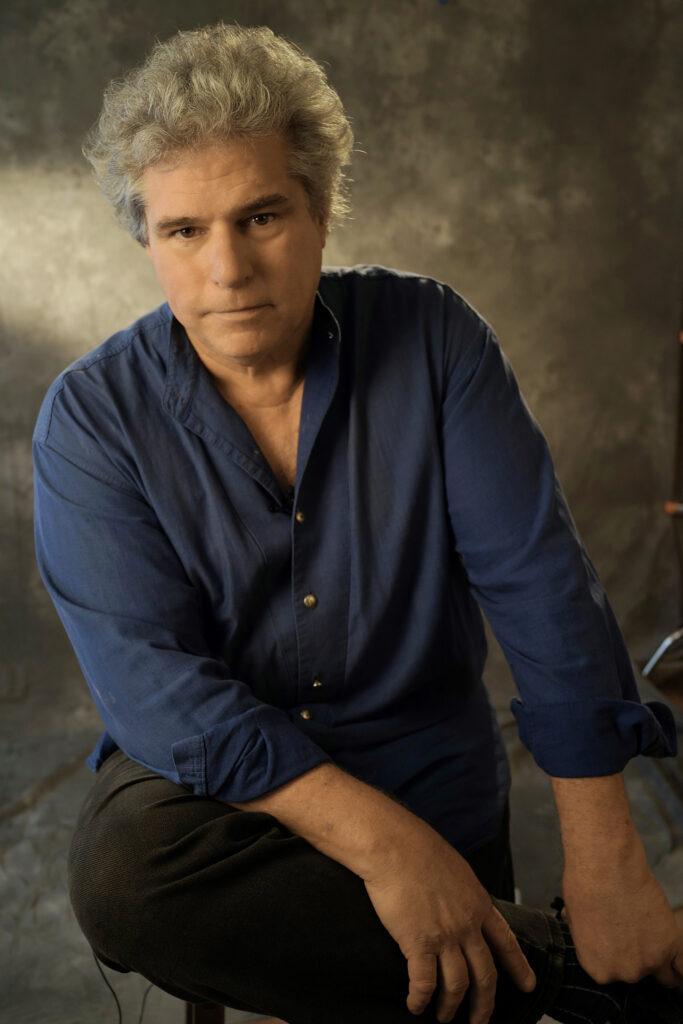

Lorenzo DeStefano

Novelist

about Lorenzo

My Story

Born in Honolulu, Hawai’i, Lorenzo DeStefano is a playwright, screenwriter, producer, director, and photographer. A member of the Directors Guild of America, he has produced and directed network series, documentaries, and narrative films, worked in U.S. and U.K. Theater, and written fiction, non-fiction, original screenplays, and adaptations.

In addition to “House Boy”, his first published novel, DeStefano is author of the short story collection, “The Shakespearean”, the essay “On Knowing Daniel Aaron” , the fact-based short story “Hitchhike”, the memoir “Visitations – Finding A Secret Relative In Modern-Day Hawaii”, “Diary of a Nobody”, a feature article for The Guardian, the photographic memoir “La Hora Magica/The Magic Hour – Portraits of a Vanishing Cuba”, and the cinema memoir “Callé Cero–An Encounter with Cuban Film Director Tomas Gutierrez Alea”.

DeStefano’s screenplays include “Lads”, “Deep Inside”, “Cropper’s Cabin”, from the novel by Jim Thompson, “Appointment in Samarra”, from the novel by John O’Hara, “Waiting for Nothing”, from the novel by Tom Kromer, and “Creeps”, from the play by David E. Freeman.

Narrative films as writer/producer include “The Diarist”, a Limited Series based on “The Inman Diary”, published by Harvard University Press, and “House Boy”, a Limited Series adapted from his novel.

Narrative films as writer/producer/director include the short film “Stairway to the Stars”, starring Sean Young and Quinton Aaron, and “Shipment Day”, an adaptation of his prize-winning play.

His feature documentaries as producer/director include “Talmage Farlow”, a portrait of the American jazz guitarist, “Los Zafiros-Music From The Edge Of Time”, about the Beatles of 1960s Cuba, and “Hearing is Believing”, about the gifted young musician and composer, Rachel Flowers.

Plays include “Shipment Day”, “Stairway To The Stars”, “Providence”, and “Camera Obscura”.

Theater directing includes “Fireflies”, by Matthew Barber, William Inge’s “Natural Affection”, Horton Foote’s “The One-Armed Man”, the world premiere of Robert Schenkkan’s “Conversations with the Spanish Lady”,

the world premiere of “Twisted Twain” by Bill Erwin, “Jitters” by David French, and his own productions of “Providence” and “Shipment Day”.

His career in motion picture film editing includes “The Blue Lagoon”, “Making Love”, “That Championship Season”, “Dreamscape”, “Girls Just Want To Have Fun”, “Thrashin’”, “Winners Take All”, “The Killing Time”, and “Gingerale Afternoon”. He was Supervising Film Editor, Producer, and Director during the 4 season/83 episode run of the ABC/Warner Brothers drama series, “Life Goes On”.

Photography credits include “Rest Homes Hawai’i”, “Leahi Hospital – Children’s Ward”, “Six Feet Under”, and “Queen of the Damned”.

His traveling exhibition, “Cubanos-Island Portraits 1993-1998”, shown extensively in Cuba, New York, Chicago, London, Havana, Los Angeles, and Vancouver, is in the Permanent Collection of the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, California, and the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami.

- How would you describe your creative process?

“HOUSE BOY” has been unlike any other writing adventure I have been on. I first encountered the true incident on which the book is based in 1995 while in London for a reading of a play of mine at the Greenwich Theatre.

The small newspaper article I read one day, about a young man’s trial for murder of his female “employer”, tapped into my existing interest in and revulsion for the phenomenon of modern slavery. What I found initially compelling was that this victim of domestic and sex slavery was a young man while the perpetrator was a middle-aged woman. This contrasted with the usual dynamic of female sex trafficking that I and many others had gotten used to.

After inquiries were made, it was arranged by the accused’s solicitor that I visit the convicted young man in Brixton prison in South London to discuss his case and interview him for a potential magazine article. In the novel, I transferred many aspects of this experience with that of Detective Jayawan Gopal, in that the day before my scheduled visit the inmate was deported to India. This was, I learned, one of the terms of his conviction for “manslaughter with provocation”, a lesser charge than “capital murder” because of the extenuating circumstance of torture and enslavement that came out at trial.

Disappointed but glad for his second chance at freedom, I tried for several months to locate this young man in Tamil Nadu State through private investigators, to no avail. This was not a person with any social profile, no footprints to trace. No amount of web surfing turned up anything.

I gave up on the piece, at least how I originally envisioned it. But this was that kind of story that gets a hold of a writer and will not let go. Unlike many of my other fact-based film & theater projects, there was very little documentary evidence to follow. There were no first person witnesses available. As a result, I decided after several years away from the piece to embark on a major creative journey and write the story as a novel.

I worked on it for many years, in between film and theater and other writing projects. On subsequent trips to the UK, I visited the location of the actual incident on Finchley Lane in the borough of Hendon, North London. I photographed every house on each side of the street, knowing that in one of these dwellings these horrific events had taken place. I observed a number trials at the Old Bailey, London’s Central Criminal Court, to familiarize myself with the UK’s completely different trial system. After inquiring of the Court if a transcript of the trial could be obtained, I was told that as a murder case these records had been sealed. I did manage, through the kind intervention of a clerk, to receive a copy of the 28- page Police Summary of the case, which proved invaluable and was the single greatest piece of research I obtained.

With this in hand, I embarked on voluminous research into a culture not my own. This was an incredibly challenging process. A better word would be daunting. I did my best to infuse Vijay’s desperate search for salvation during his ordeal in the Tagorstani’s house with the kind of Hindu and Tamil prayers I felt he, as a man of faith, would cling to for inner strength. I found out quickly that Indian culture is fiendishly complex, especially for outsiders. I was determined, as a western writer, to get the facts and the history and the language right. This took a very long time and much trial and error.

============================================================

- You are not South Asian, but you have lots of South Asian characters, aside from the protagonist, in the book. What motivated you to write this one? Do you have first-hand experience in witnessing a human trafficking incident?

While I believe that writers should be able to explore any subject under the sun, no matter their ethnicity, there is a special responsibility when the story is outside one’s life and cultural experience. From the beginning I knew that a major part of completing the manuscript would be to consult with a South Asian author or academic to help me eliminate anything inauthentic or just plain wrong. Through Atmosphere Press I met Falguni Jain, a young writer and book reviewer from Maharashtra, India. Falguni was extremely helpful in making certain that the many references to South Asian cultural & religious content were correct and that the rigorous rules of the caste system, down to names and customs and social attitudes, were authentic and indisputable.

The trust and support of many people have gone into this book’s completion, including everyone at Atmosphere Press for seeing the promise in the book and guiding me expertly towards publication. Most importantly, I need to send thanks and respect to “EMG”, the man I never met, who actually lived this story.

Other than my efforts to meet “EMG”, I do not have any first-hand experience with human trafficking. I guess I should consider myself fortunate in this, though I do feel that by immersing myself in this story for all these years I have attempted to come as close as I can to what it would be like to be in a situation like Vijay’s, though nothing in a book, however well-executed or intentioned, can compare to what goes on in real life.

=========================================================

- Detective Inspector Gopal, like Vijay, is a South Asian character. Was this intentional? Do you think Vijay’s case would have been handled differently if the D.I. was not of the same race as the accused?

The character of Jayawan Gopal was always intended to be South Asian. I felt that his experience as an upper caste Brahmin, rising in the ranks of the Metropolitan Police, provided the ideal contrast to Vijay’s tragic experience in the new world. I do feel that the dynamic between these two would have been vastly different and much less interesting if the Detective Inspector were a white man or woman. Empathetic as he/she may have been, they could never have gotten close to understanding who they were dealing with. D.I. Gopal has a hard enough time despite he and Vijay both being from India. Their life experiences are worlds apart, universes apart in fact.

I also found that Gopal’s process in getting to know and understand Vijay mirrored my own attempts as a writer to meet the real character on which Vijay is based. I found it easier to find an overlap between my own frustrated experience trying to meet this young man in Brixton Prison in 1995 with Gopal’s attempts over the course of his investigation and the subsequent trial and conviction to get close to someone he had very little in common with, despite their shared nationality.

============================================================

- Why focus on Indian culture and its people? I’m sure there are other races who fall victim into and perpetrate human trafficking. When you did your research, was there a huge turn out of Indians among others?

In the process of writing “House Boy”, I came to understand a very sad reality – that domestic and sex slavery knows no cultural or geographic boundaries. This kind of oppression seems to lie so deep in the human DNA as to be something eternal, insidious, fueled by greed and a streak of cruelty beyond what most people are capable of, not to mention comprehend.

The criminal elements at work here should not be discounted, which is why I made Binda and her gang at the Pandit Advisory Group such experts at “affinity fraud”, the nearly foolproof method of criminal enterprise based on people lowering their guard when dealing with those they feel are like them and would, therefore, never abuse their trust.

All this makes for an unholy alliance of factors that create the roles to be played in this sinister drama called modern slavery – the oppressed and the oppressors. It’s like an epic play that never ends. The curtain on these actions never rises or falls. The drama just goes on and on, year after year, decade after decade, millennia after millennia, like a marathon session in this madhouse called humanity.

============================================================

- As a follow-up question to the last one, could you run us through the research you did? Where did you go, who did you talk to, and what did you find out?

I consulted with people at Anti-Slavery International in the U.K., Free The Slaves in the U.S., Human Rights Watch, and Kalayaan, a London-based charity which works to provide practical advice and support for the rights of migrant workers.

I also read a number of books on the subject of modern slavery, the most important being Kevin Bales’ “The Slave Next Door” and “Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy”.

I watched a number of video news stories from India and all over the world covering cases of modern slavery. I also watched many times the amazing film, “Bandit Queen”, about the notorious Dalit woman, Phoolan Devi, who formed a gang of mostly male soldiers and took violent revenge on the upper caste tormentors who had repeatedly raped her at any early age and beat and humiliated her and her family over many years. After receiving amnesty, Devi stood for election to Parliament as a candidate of the Samajwadi Party and was twice elected as a Member of Parliament. She served in this capacity between 1996 and 2001, the year she was assassinated outside her home by relatives of those she and her supporters had killed years before for revenge.

Researching “HOUSE BOY” was a fascinating but often unpleasant experience that exposed me to a very bloody and tumultuous history, one lasting thousands of years and crossing borders like an unstoppable virus, a pernicious disease.

============================================================

- Aside from the soulless people who make human trafficking a business, could we actually attribute the blame to its victims? Is there some kind of brainwashing that happens or are people who fall into this really naive in nature? Because from what I’ve read, Vijay seems to be clever. He may be poor, but he’s not dumb. How could someone like him fall for this huge scam?

I don’t believe that it’s right in cases like this to blame the victims. Probably it’s never the right thing to do. It’s like saying that a woman who is raped brought it on herself. This kind of violence and human rights abuse is deeply rooted in the psyches of the perpetrators, who may themselves not know why they are doing these horrible things. Something sets in called “caste privilege”, a kind of belief system that Binda and her son and other Brahmin characters in the books are definitely afflicted with. There are many victims here, but the true victims of serf suffering are those who are enslaved, not their keepers.

Vijay, as with the real character he is based on, struck me as an innocent in search of something we all hope to get out of life, some just treatment and reward for the work we do. He was too trusting, was in way over his head. And due to the kind of “affinity fraud” perpetrated on him by Mr. Gupta and Mr. Gopalan of the Better Life Employment Agency in Chennai, he falls for their glowing promises of a better life in the U.K. where he can fulfill his dream of earning money for his sisters’ dowries and improve the lot of his parents back in Chettipattu.

========================================================

- Again, as a follow-up to the last question. Why did you make Vijay stay at the Tagorstani residence even after the “deed”? He knows one way or another, this is going to be connected to him. He must have been eager for freedom. He must have wanted to ask for help and escape to contact the authorities. But he stayed – why?

At some point in Vijay’s captivity, as we have seen in other extreme cases of enslavement, “Stockholm Syndrome” sets in, which explains in part why he stays in the house on Finchley Lane after he has dispatched Binda. He knows no other place to go in this place called England. In a way he is finally at peace, a peace he knows will not last long, with Ravi Tagorstani soon to return from his business trip to Blackpool and demand answers about his mother’s whereabouts. Vijay knows he has committed a sin, no matter how justified, and that he will have to pay a heavy price for this. Try as he does to conceal his guilt with the most outlandish lies to Ravi and to the authorities, he, as an essentially honest man, has no choice but await his punishment for what he has done against the laws of God and Man.

=========================================================

- Aside from exposing this harsh reality, is there another purpose for writingHouse Boy? Is this some kind of protest to wake people up and encourage people to do more to finally end human trafficking?

During this entire process, I became fascinated by the way the caste system seemed to jump so effortlessly from the ancient world to the so-called “New World”. Over many years of writing and rewriting this piece, a major motivation was to try and nail down as much as possible why this happens in human society and how, with this book, there may be a way to illuminate this situation for the better.

Despite my long experience in documentary filmmaking and as a writer of non-fiction, I did not want to write a rigidly “factual” piece. I felt that that being constrained by documentary facts, of which I had very few anyway, would not be the best way to create the scenes and situations I felt were necessary to paint a dramatic picture of this year in the life of Vijay Pallan. I was more after something that would keep me, as a reader, engaged from start to finish.

The risk with a piece like this is that you can exhaust the goodwill of the reader by being too relentlessly dark about what is taking place. Exhaustion sets in. Readers have been exposed to so much horror, so much human indignity, that the mere mention of something like modern slavery or human trafficking can send people running for something more palatable to read or experience. I had to find a way, and I hope I have, to make Vijay’s story so compelling, so captivating and powerful, that most people would tolerate the darkness of the piece in search of the light that does exist within it, the light of hope that can never be allowed to be extinguished.

What happens to Vijay and everyone else in this novel is no fairy tale. Despite there being no truly happy endings, I wanted “House Boy” to have some redemptive qualities. Largely through Inspector Gopal’s encounters with Vijay Pallan, we learn much about the harsh realities of human trafficking, the boundless capacity for human pain, and the ultimate blessing of even one man’s survival.

=========================================================

- Vijay eventually got his justice. I’m curious if the other people in Sami Appan’s van also got theirs? Was the Pandit Group investigated and dissolved?

That’s a very interesting question and one I have not thought about before. In a tragic way, these people that Vijay meets briefly in the darkened interior of Sami Appan’s van are, like him, nameless, faceless people being transported for purposes beyond their initial comprehension. They are there to feed the labor needs of people who see them not as fellow human beings but as creatures of service. Like millions of other citizens of the world, they count for next to nothing to those who control their destinies. They are fodder for the machine that is human exploitation. It’s a very sad and troubling fact that the vast majority of victims of crimes like this, as in Vijay’s case, never achieve any semblance of justice. They and their suffering become invisible to us. Their predicament is so enormous it is beyond our ability to process or comprehend.

As for the Pandit Advisory Group set up by Binda, I indicate in the book that it has been thoroughly exposed because of Vijay’s trial and Sheela Atwal’s damning testimony. As a result, this particular affinity scam and the people who ran it, namely Al Mohindar, Ray Nabob, and Sheela Atwal, will be serving considerable prison time for their fraudulent activities, though I did not go into too much detail about their fates other than to indicate that they will indeed be paying some price for their actions.